Don’t you see the plants, the birds, the ants and spiders and bees going about their individual tasks, putting the world in order, as best they can? And you’re not willing to do your job as a human being? Why aren’t you running to do what your nature demands?

— Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, 5.1

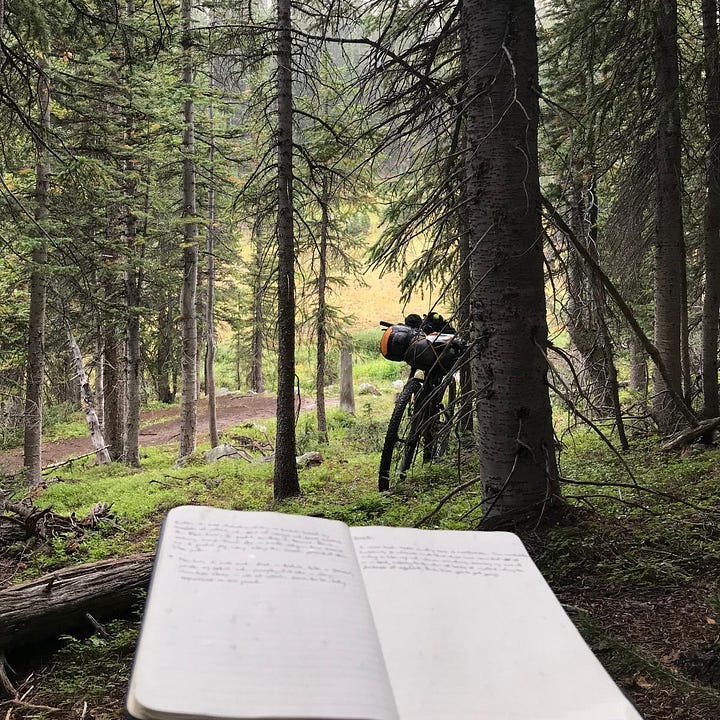

One night, a few years back, I found myself camping just below the summit of Jarosa Mesa, a table-topped peak that sails some 12,000 feet above sea level, in the heart of Colorado’s San Juan Mountains. I was alone, as I had been for the better part of two weeks, cycling my way from Denver to Durango on the Colorado Trail. The journey was about 550 miles long, and it brought me through some of the most rugged and remote wildlands in the state.

The views were beautiful, but the magnitude of the mountains, and the profound difficulty of traversing them, often left me too tired to appreciate the scenery. I felt something like Sisyphus as I climbed up and over mountain after mountain, only to find higher, more challenging peaks on the other side. My bike, my boulder, caught up in an endless cycle of cycling over peak after high-alpine peak. I sometimes thought of a line from Camus, during these sustained and tiresome climbs: “One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

It was exhausting.

I felt particularly exhausted that night, camped out on the alpine tundra on the western slope of Jarosa Mesa. I was running low on food, many miles from the nearest town, sunburnt and cotton-mouthed and alone. Totally, profoundly, completely alone. No signs of life. No signs of civilization. Nothing on the landscape suggested what century I was living in, save for my tent and my bicycle and a blinking red light on an antenna atop a distant peak.

In every direction, a chain of jet-black mountains ringed the skyline, their peaks serrated like the teeth of a saw. No trees grew on the mountain where I camped. Up there, the air is too cold — atmospheric pressure, moisture, and oxygen levels too low — for trees to grow. The sky was black and crystalline and studded with the dancing light of distant suns. Shooting stars shot across the sky like flaming arrows, igniting and combusting in plumes of gas and dust. Sunlight gleamed on the face of the moon, casting a faint, soft light upon me as I sat beside my tent, my headlamp illuminating the pages of Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations.

“Watch the stars in their courses and imagine yourself running alongside them,” the passage read. “Think constantly on the changes of the elements into each other, for such thoughts wash away the dust of earthly life.”

Marcus Aurelius Was More Than a Stoic

Aside from my guidebook (and a teeny tiny little field guide to Rocky Mountain flora and fauna), Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations was the only book I brought with me on that trip along the Colorado Trail. I figured reading the book there and then would help me cultivate the strength and resilience and mental fortitude I’d need to keep going, up and down mountains, day after day, for two weeks straight. That is why many people read Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations (and the works of other Stoic philosophers), I believe: in search of strength while navigating the treacherous terrain of life itself.

“You have power over your mind,” Marcus Aurelius wrote, “not outside events. Realize this, and you will find strength.”

This is the essence of Stoicism. We don’t have power over most of what life throws our way, but we have power over how we respond to life’s obstacles. So much of Stoic philosophy echoes this lesson.

“We suffer more in imagination than in reality,” Seneca wrote.

“It’s not what happens to you,” Epictetus said, “but how you react to it that matters.”

It’s quotes like these that you tend to see on Instagram and TikTok and X, and in articles and blog posts and books, and for good reason. Stoic philosophy cultivates strength, courage, and self-control, and these qualities carry over to just about every nook and cranny of your life. Whether you’re riding a bike across Colorado’s Rocky Mountains, studying for a final exam, climbing the corporate ladder, making a career change, going through a breakup, raising a child, or grieving the death of a loved one, these Stoic teachings apply.

A little bit of Stoic philosophy goes a long way toward fortifying the mind. But taken to its extreme, Stoicism begins to feel . . . cold. Callous. Soulless. Indifferent.

In his Meditations, for example, Marcus Aurelius reminds himself “not to display anger or other emotions.”

“If you pursue pleasure,” Marcus Aurelius wrote, “you can hardly avoid wrongdoing . . .”

“Sexual intercourse,” Marcus Aurelius declared, “is no more than the friction of a membrane and a spurt of mucus ejected.”

First of all: gross.

Second: Where’s the life in all of this philosophizing? Where’s the heart? Where’s the empathy and sensitivity and compassion?

Third: I don’t know about you, but sex is a whole lot more meaningful to me than the rubbing together of membranes and the spurting of bodily fluids, but I digress.

Reading quotes like these, it’s easy to think of Marcus Aurelius as a kind of David Goggins of antiquity. Stay hard. Suppress your emotions. Pleasure and joy and enjoyment are weaknesses not to be indulged in. On the surface, Stoicism can seem like a solemn, dreary philosophy. Even the word “stoic” tends to have a negative connotation in today’s day and age. When we say that somebody is stoic, we often mean he’s emotionless. Detached. A walking, talking statue. One definition of “stoic” actually reads: “[A] person who represses feelings or endures patiently.”

There’s more to Stoicism than “staying hard,” however. Stoicism isn’t telling us to repress our emotions entirely; it’s reminding us not to be ruled by them. “The mind is a wonderful servant but a terrible master,” as the writer Robin Sharma put it. I think most Stoics would agree.

The philosophy of Marcus Aurelius, in particular, runs far deeper than this kind of hard-nosed self-help of the ancient world. Marcus Aurelius didn’t write his Meditations with the intention of helping anyone but himself. Meditations is a collection of reminders that Marcus Aurelius wrote to himself between 161 and 180 CE, when he was the emperor of Rome. Meditations is Marcus Aurelius’s personal diary, and it’s something of a miracle that the book was discovered and preserved for posterity (but that’s a story for another day). Marcus Aurelius wrote his Meditations in his most private and vulnerable moments. Read the book in its entirety, and you’ll see that the man had a soft side. Far from the robotic and unfeeling person we imagine a “Stoic” to be, he was thoughtful, sensitive, compassionate, appreciative of life’s many beauties, large and small.

Marcus Aurelius didn’t even consider himself to be a Stoic, in fact. In his translation of Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations, the scholar Gregory Hays wrote:

Marcus Aurelius is often thought of and referred to as the quintessential Stoic. Yet the only explicit reference to Stoicism in Meditations is phrased in curiously distant terms, as if it were merely one school among others. The great figures of early Stoicism are conspicuous by their absence. Neither Zeno nor Cleanthes is mentioned in the Meditations, and Chrysippus appears only twice — quoted once in passing for a pithy comparison and included with Socrates and Epictetus in a list of dead thinkers. This is not to deny the essentially Stoic basis of Marcus’s thought, or the deep influence on him exercised by later Stoic thinkers (most obviously Epictetus). If he had to be identified with a particular school, that is surely the one he would have chosen. Yet I suspect that if asked what it was that he studied, his answer would have been not “Stoicism” but simply “philosophy.”

Marcus Aurelius was more than a Stoic, in other words.

Marcus Aurelius was a natural philosopher.

The Natural Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius

Nature played a central role in Marcus Aurelius’s philosophy. Vast portions of his Meditations are filled with admiration for and adoration of the natural world. The workings of nature seem to have influenced Marcus more than Stoicism, in fact, or any other school of philosophy that he studied (and he studied many schools of philosophy). The word “nature” appears in Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations more than 150 times. The word “Stoic,” by contrast, appears only once. Epictetus’s name — the Stoic philosopher who influenced Marcus Aurelius more than any other — appears a mere six times.

“We should remember that even Nature’s inadvertence has its own charm, its own attractiveness,” Marcus wrote. “The way loaves of bread split open on top in the oven; the ridges are just by-products of the baking, and yet pleasing, somehow: they rouse our appetite without our knowing why.”

Or how ripe figs begin to burst.

And olives on the point of falling: the shadow of decay gives them a peculiar beauty.

Stalks of wheat bending under their own weight. The furrowed brow of the lion. Flecks of foam on the boar’s mouth.

And other things. If you look at them in isolation there’s nothing beautiful about them, and yet by supplementing nature they enrich it and draw us in. And anyone with a feeling for nature — a deeper sensitivity — will find it all gives pleasure. Even what seems inadvertent. He’ll find the jaws of live animals as beautiful as painted ones or sculptures. He’ll look calmly at the distinct beauty of old age in men, women, and at the loveliness of children. And other things like that will call out to him constantly — things unnoticed by others. Things seen only by those at home with Nature and its works.

Marcus Aurelius was a man to stop and smell the roses, so to speak; to notice the subtle, often overlooked beauty of the natural world. Marcus Aurelius was a man who was “at home with Nature and its works.” Even filth and decay were beautiful to Marcus Aurelius’s eyes: a rotting olive, a withering stalk of wheat, the foam on the lips of a salivating boar. These things were beautiful to Marcus’s eyes because they, too, are natural; because they supplement and enrich the workings of nature. And Marcus Aurelius saw his fellow human beings with this same sense of reverence and admiration that he viewed the natural world. To Marcus Aurelius, the youthful energy of a child was every bit as lovely as the blooming of a flower; the graying hair and wrinkled skin of an aging woman every bit as beautiful as that flower’s wilting.

“Everything in any way beautiful has its beauty of itself,” Marcus wrote, “inherent and self-sufficient: praise is no part of it. At any rate, praise does not make anything better or worse. This applies even to the popular conception of beauty, as in material things or works of art. So does the truly beautiful need anything beyond itself? No more than law, no more than truth, no more than kindness or integrity. Which of these things derives its beauty from praise, or withers under criticism? Does an emerald lose its quality if it is not praised? And what of gold, ivory, purple, a lyre, a dagger, a flower, a bush?”

Marcus Aurelius didn’t just admire nature’s beauty; he drew inspiration from it. In the same way that emeralds and flowers and bushes don’t need praise and acclaim to validate their beauty — their inherent value and worth — he didn’t either.

“Then what is to be prized?” Marcus asked himself.

An audience clapping? No. No more than the clacking of their tongues. Which is all that public praise amounts to — the clacking of tongues.

So we throw out other people’s recognition. What’s left for us to prize?

I think it’s this: to do (and not do) what we were designed for. That’s the goal of all trades, all arts, and what each of them aims at: that the thing they create should do what it was designed to do. The nurseryman who cares for the vines, the horse trainer, the dog breeder — this is what they aim at. And teaching and education — what else are they trying to accomplish?

So that’s what we should prize. Hold on to that, and you won’t be tempted to aim at anything else.

This is a teaching that applies to every human being’s life and work, and it is Stoicism in action. What’s more important than the praise you receive for what you do is the quality of what you do, whatever it is. You don’t need a National Medal of Arts to make beautiful art. You don’t need a National Book Award to write a beautiful book. You don’t deserve a Nobel Peace Prize for being a decent human being. You don’t make art or write books or treat people with kindness and compassion and respect for praise or fame or acclaim, or some other ulterior motive. You do these things because you love them, because these things are what your own nature demands of you. You do these things because they are the right thing to do, by your own definition, according to your own nature.

“Don’t you see the plants, the birds, the ants and spiders and bees going about their individual tasks, putting the world in order, as best they can?” Marcus Aurelius mused in his Meditations. “And you’re not willing to do your job as a human being? Why aren’t you running to do what your nature demands?”

Every living organism is fulfilled when it follows the right path for its own nature.

— Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, 8.7

Marcus Aurelius saw nature as a teacher, a guiding force that can help us navigate our lives with meaning and purpose in the here and now. Just as a bee — doing what its nature demands, following the right path for its own nature — pollinates flowers and maintains the harmony of its ecosystem, so too can we.

Each and every one of us are a part of something greater and more important than ourselves, whether we like it or not. We are a part of our families, our friend groups, our societies, our ecosystems. Our every thought, word, and action impacts the people in our lives and the world around us, for better or worse. And we therefore wield the responsibility to think and speak and act for a greater good. When we think and speak and act to the detriment of the world that surrounds us, we degrade and demean ourselves as well. “What injures the hive injures the bee,” as Marcus Aurelius wrote. Conversely, when we think and speak and act with kindness, with compassion, with strength, with courage, with justice and humility and wisdom and self-control, we benefit ourselves and the world as a whole, in ways large and small.

“We are made for cooperation,” Marcus Aurelius wrote, “like feet, like hands, like eyelids, like the rows of the upper and lower teeth. To act against one another then is contrary to nature; and it is acting against one another to be vexed and to turn away.”

And “cooperation” means accepting what nature assigns you — accepting it willingly.

— Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, 10.8

The same laws of nature that govern the lives of plants and birds, of ants and spiders and bees, govern human lives as well, Marcus Aurelius believed. He called this governing principle the logos. (The idea of the logos comes from the Greek philosopher Heraclitus, who lived around 540–480 BCE.) Marcus Aurelius believed that the logos was rational, intelligent, divine. He believed that the logos was omnipresent, omnipotent. He believed that the logos was the source of everything in existence, that it permeated all things and tethered all things together. (“Everything is interwoven,” he wrote, “and the web is holy; none of its parts are unconnected. They are composed harmoniously, and together they compose the world. One world, made up of all things. One divinity, present in them all.”) He believed that the logos exists to organize and harmonize the universe, to move it all forward toward some higher purpose that we could never wrap our all-too-human minds around. And he believed that the purpose of our lives was to live in harmony with the logos, that to follow the “right path” for our “own nature” was to live out our fate, to fulfill our destiny.

You have functioned as a part of something; you will vanish into what produced you.

Or be restored, rather.

To the logos from which all things spring.

By being changed.

— Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, 4.14

“What happens to each of us is ordered,” Marcus wrote. “It furthers our destiny.”

For there is a single harmony. Just as the world forms a single body comprising all bodies, so fate forms a single purpose, comprising all purposes . . . It may not always be pleasant, but we embrace it — because we want to get well. Look at the accomplishment of nature’s plans in that light — the way you look at your own health — and accept what happens (even if it seems hard to accept). Accept it because of what it leads to: the good health of the world . . .

“There are two reasons to embrace what happens,” Marcus continued. “One is that it’s happening to you. It was prescribed for you, and it pertains to you. The thread was spun long ago, by the oldest cause of all.”

The other reason is that what happens to an individual is a cause of well-being in what directs the world — of its well-being, its fulfillment, of its very existence, even. Because the whole is damaged if you cut away anything — anything at all — from its continuity and its coherence. Not only its parts, but its purposes. And that’s what you’re doing when you complain: hacking and destroying.

Frankly, I’m not sure that I agree with Marcus Aurelius’s views on things like the logos, fate, and destiny, but I don’t disagree either. I’m scientifically-inclined, but I’m spiritually curious, open to the idea that there might be more to life than atoms and molecules and subatomic particles, chaos and coincidence and random chance. Deep down, I believe this to be true, though I don’t know what label to put on this higher power. Stoics called it the logos. Hindus call it Brahman. Taoists call it the Tao. Buddhists call it Buddha Nature. I don’t know what to call it.

This article isn’t about my own philosophy and spiritual views, however; it’s about Marcus Aurelius’s philosophy, his spiritual views. I’m not suggesting that you accept all of Marcus Aurelius’s beliefs on blind faith, and I don’t think he would either.

“Look inward,” Marcus Aurelius might tell you. “Don’t let the true nature or value of anything elude you.”

Before long, all existing things will be transformed, to rise like smoke (assuming all things become one), or be dispersed in fragments.

— Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, 6.4

Marcus Aurelius wrote endlessly of seeing the “true nature” of things, himself included. He reminded himself constantly of life’s finitude. This didn’t depress him, however. It brought him back to the present moment, to the here and now, and motivated him to live with meaning and purpose with the time he had.

Of “Human Life,” Marcus wrote:

Duration: momentary. Nature: changeable. Perception: dim. Condition of Body: decaying. Soul: spinning around. Fortune: unpredictable. Lasting Fame: uncertain. Sum Up: The body and its parts are a river, the soul a dream and mist . . .

Life and our experience of it is short-lived. Life is flux. At any given moment, the cells that comprise our bodies are dividing and replicating. Molecules that we eat, drink, and breathe become us, and those that we once were disintegrate and merge with the exterior world. Our DNA breaks and mutates. Our telomeres shorten. The wear and tear of our organs leaves behind cellular debris to be cleaned and cleared away by still other bodily functions. As we move through life, through space and time, we move ever closer toward death. As Epicurus (a philosopher whom Marcus Aurelius quotes in his Meditations) wrote: “the art of living well and dying well are one.”

“Death,” Marcus Aurelius wrote, is “something like birth, a natural mystery, elements that split and recombine. Not an embarrassing thing. Not an offense to reason, or our nature.”

In short, know this: Human lives are brief and trivial. Yesterday a blob of semen; tomorrow embalming fluid, ash.

To pass through this brief life as nature demands. To give it up without complaint.

Like an olive that ripens and falls.

Praising its mother, thanking the tree it grew on.

Human life is brief and trivial, but beautiful nonetheless. Like an olive that grows and ripens and falls and decays, life is beautiful because it is fluid, fleeting, ephemeral. Death, as Marcus Aurelius saw it, is the culmination of life, the completion of it. Without death, life means nothing. And like a storm that comes to pass, life doesn’t last forever.

“Be satisfied if you can live the rest of your life, however short, as your nature demands,” Marcus wrote. “Focus on that, and don’t let anything distract you.”

“Observe constantly that all things take place by change,” Marcus urges us, “and accustom thyself to consider that the nature of the Universe loves nothing so much as to change the things which are, and to make new things like them.”

“Don’t be anxious,” Marcus reminds us. “Nature controls it all.”

And before long you’ll be no one, nowhere . . .

. . . Concentrate on what you have to do. Fix your eyes on it. Remind yourself that your task is to be a good human being; remind yourself what nature demands of people. Then do it, without hesitation, and speak the truth as you see it. But with kindness. With humility. Without hypocrisy.

“Do not act as if you were going to live ten thousand years,” Marcus Aurelius wrote. “Death hangs over you. While you live, while it is in your power, be good.”

Addendum: The Right Book at the Right Time

I had read Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations half a dozen times before setting out on that trip across the Colorado Trail. I try to reread the book once a year, whenever life gets tough and I find myself drifting from my values as a human being, losing perspective, lacking clarity. I read the book for the first time shortly after my father was diagnosed with brain cancer, and I was teetering on the edge of dropping out of college. I read the book again after my father had died, and my family had fractured and fallen apart. I read the book yet again when I decided to quit my job to pursue writing full-time.

Meditations, like all great books, is a mirror. Every time I revisit it, I notice something that I had missed on earlier readings, something that reflects some aspect of my life and mind in the here and now.

And it wasn’t until I read the book out there on the Colorado Trail that I noticed the central role that nature played in Marcus Aurelius’s philosophy. I suppose my surroundings had something to do with it. For two weeks, I was surrounded by nothing but rivers and streams, mountains and clouds, plants and birds, ants and spiders, bees and trees. In that environment, immersed in nature, all the reverence and admiration that Marcus Aurelius had for the natural world really jumped out at me.

Much of that reverence and admiration for nature made its way into me, too. Out there on the Trail, I came to see myself, more clearly than ever before, as a part of the natural world, a part and process of nature itself. And I came to see the Colorado Trail as something of a metaphor for life itself — the right path for my own nature, so to speak. I had spent so much of my life up to that point trying to conform to some vague notion of who and what I thought I should be. Reading Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations, at that time and place in my life, helped me cultivate a newfound independence, to grow into who and what I really am, to Individuate, to become my Authentic Self. It’s fitting that the word nature comes from the Latin root natura, which means “to be born.” Reading Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations on the Colorado Trail set me on a path of self-discovery that I continue to follow to this day, long after my travels on the Colorado Trail came to an end.

And just as every mile of the Colorado Trail passed upon new land, offering new vistas of wide horizons and novel landscapes, life, too, is a thing of flux. From the passage of time to the cycles of atoms and molecules that make life possible, life is a process of constant, unrelenting change. Life is a dash between birth and death, just as the Colorado Trail is a line on a map with a beginning and an end.

What it all means is found in the space between.

This is truly a wonderful mediations on the Meditations. So true, what's matter is doing what we are here to do between birth and death. that is living well and so dying well; as Socrates said all life is truly a preparation for a good death

This is really amazing. Realizing the finitude of life brings us to the now and here. Sitting in a library in a town in India, reading someone's Colorado trail experience with a Roman emperor's book and being able to relate to every word of it is just mind-boggling for me. How connected are we across time and space!